The Elusive American Dream🔎🕵️♂️

The paradox between disbelief and hope towards the American Dream in Fences and A Raisin in the Sun is a greater reflection of the instability marginalized Americans hold onto their opportunities, ingrained discrimination in the 1950s, and current injustice.

Both Fences and A Raisin in the Sun are set in 1950’s America. History tells us that it was a time where people felt reassured by America’s economic stability, which was largely contributed by the influx of military spending. Americans held more purchasing power and contributed great amounts to instill materialism as a symbol of wealth and well-being. The American Dream began to alter its image.

We see this slight shift in two artworks.

Both the Younger and Maxson family reside in deep poverty; they are excluded from the increasingly demanding societal expectation of possessing material goods and the necessities money brings. Money becomes the push and pull, an elusive ideal symbolizing a critical aspect of the newly corrupted American Dream, one that promised wealth and purchasing power.

The word money appears in A Raisin in the Sun 39 times.

The origins of the Younger family’s money revolve around old Walter’s life insurance. As Walter states, “That money is made out of my father’s flesh…” (Hansberry 575). The cold colored green paper often associated with greed and selfishness becomes alive--a symbol of a father’s undeniable selflessness for his family. The stark dichotomy between the two interpretations demonstrates the lower class struggle for an essential that can’t be replaced. Dreams for money are humanized. Money is characterized as generations of life and death, “working and working and working like somebody’s old horse...killing himself….”(Hansberry 577). For those in a lower class experiencing discrimination in the 1950’s, money--a motif of the American Dream--becomes even more than purchasing products, it takes on a precious ideation like a piece of gold; money not only contains the dreams of the individual, it also contains the dreams and sacrifices of the individual’s ancestors.

This connotation is also emphasized in Fences through Gabe’s VA medical benefits for his service in World War II. Again, Gabe had lost his own flesh and blood for the money to appear. Only when one loses their body will a mirage of the ladder of success appear, a disturbing truth. “If my brother didn’t have the metal plate in his head...I wouldn’t have a pot to piss in or a window to throw it out of. And I’m fifty-three years old.”(Wilson 1603).

The temptation of prosperity and achieving the American Dream manifests itself in Walter because the stakes intensify as he grapples with the dependency of both young and old. He is investing in his father’s life and expectations to manipulate poverty's overwhelming odds into a life of opportunities for his son. “...all right son it’s your seventeenth birthday...tell me where you want to go to school and you’ll go. Just tell me, what is it you want to be--and you’ll be it…”(Hansberry 577). Pressure from the engulfing forces of the American Dream and a chance at economic mobility create a simplistic illusion on winning the Dream. The insurance money paves a way for a pawn to participate in a game of chess. “...Walter's unabashed obsession with the insurance money as a key to instant affluence fits the materialistic priorities of the...dream. In presenting the moral conflict between the spiritual promises of the dream ideal and the frank materialism of the impoverished dreamer, Hansberry is being faithful to the cultural psychology of American poverty…”(Brown). Walter, impoverished from the taste of success, is understandably delusional in hope due to the minuscule opportunities and immense burden on his shoulder as an obligatory protector of his family. “I tell you I am a man--and I think my wife should wear some pearls in this world!”(Hansberry 583).

James Trunslow Adams, the author who coined the phrase the American Dream, asserts, ““dream of a land...with opportunity for each according to his ability or achievement””(Kamp 79). Troy possessed the ability to play in the Major Leagues, but the Dream’s promises did not provide. The treacherous exclusion of hope intertwined with the American Dream becomes an internalized reality for many Americans left out of its cliché optimism. As time continues, the trend of downward hope becomes deeply apparent.

Troy’s complexity lies between his perceived dishonest actions and character exposition. Being African American and impoverished, his origins have carved a blocked channel of opportunities inciting frustration and dissatisfaction later in life. The cruel halt of hope parallels fate, a paradox to the championed freedom and rags to riches story encompassing the American Dream. His battleground differs from the clean unbridled baseball stadium ground and Bart Giamatti’s declarations. Troy’s footing on the American Dream absorbs into the rough surroundings of his detached battlefield--the one behind his house where the baseball is a ball of old rags and the bat is rough. In the exposition of his life, he has been designated with a different field in the irony of the “equal” sport of baseball where ability determines outcome. Yet, the outcome is corrupted with racial injustice. “Indeed, only after Troy's death at the end of the play, when his fence is completed and when his daughter Raynell plants a small garden in front of the house, is there even a suggestion of a walled paradise”(Koprince 204). Varying tension in the strings of predetermined outcomes and an eternal struggle for the power to loosen the threads drags allurement into betrayal.

Tenacity and Struggle

“For African-Americans, as for most people in the United States, their relationship with the American Dream is far more complex than one of either uncritical acceptance or rejection: we are continually coming to terms with the tenets of the Dream...” (Haggins 78). The American Dream exudes an elusive ambiguity.

Walter’s development into “manhood today”(Hansberry 586) by not succumbing to the pressure of white power is countered by him and his family’s unclear economic stability. He still isn’t able to achieve, remaining a chauffeur with weak future opportunities. Where there is personal development and acceptance in oneself, there lies reality and pain. The Younger family moves into a white neighborhood expanding racial integration, but even Hansberry foreshadows that they are just another Black household that could be easily bombed the next day.

In Fences, the Maxon family chooses to forgive Troy and send him to the Heavens. It doesn’t highlight an adaptation to the American Dream where Troy intervenes in his fate and becomes a wealthy and moral patriarch. The fence is completed to symbolize an embracement of internal preservation and dependency of family. Hope is created not through the stereotyped success of the American Dream but a cultivation of belief and strength in relationships with one another.

These plays remind Americans of the residual repetitions of the American Dream’s disparities and the strength of internal hope within its characters and within the people the American Dream hasn’t considered. For without hope, survival in the future seems daunting and unlivable. With years of abrasion, African Americans and other minorities create their own perseverance.

One could say that the American Dream is not alive anymore and dissociated from modern society. But it resides as people long for an identity to belong, a foundational right as an American. The Dream has ingrained itself into American’s societal structure; it has sustained through American culture and media. However, as Hansberry and Wilson display through the ebb and flow of their characters’ interactions with the American Dream, readers are prone to realize the underlying tenacity in Cory, Troy, Walter, Ruth, Rose against a discriminatory society. They will fall and rise as humans, but they will continue to make the best out of their situations.

Their hardship subtly warns us of the cruelty in overlooking the duality of established American ideals: simplistic assumptions that achieving America’s core values of social and economic mobility is equal and just for all.

In a study conducted in 2020 by Gallup Poll, “24% of both Black and Hispanic respondents reported experiencing workplace discrimination, far higher than the portion of white respondents (15%)”(Porterfield 5). We witnessed huge American corporations like Conde Nast release statements apologizing for tokenizing people of color in their Youtube videos while hypocritically initiating performative activism on their social media to support the Black Lives Matter Movement. Bon Appetit’s management signed contracts with white contributors to provide wages when they appeared on camera, ignoring the people of color who appeared equivalent hours without compensation. This is only just those who have appeared on media; there exist millions of individuals that live anonymously who encounter subconscious and conscious bias from society. Killings of African Americans have further exposed America's unresolved racial tensions and inconsistencies. Similar to the intrinsic workplace discrimination Troy experiences as a garbage worker where driving positions were only offered to white individuals, America has not escaped its history in the workplace today.

Foundational aspects of equality are still being violated even as time passes. Fences and A Raisin in the Sun voice a compatible truth to current society--the “encompassing” American Dream still remains a fleeting complexity to those who dream but are underrepresented.

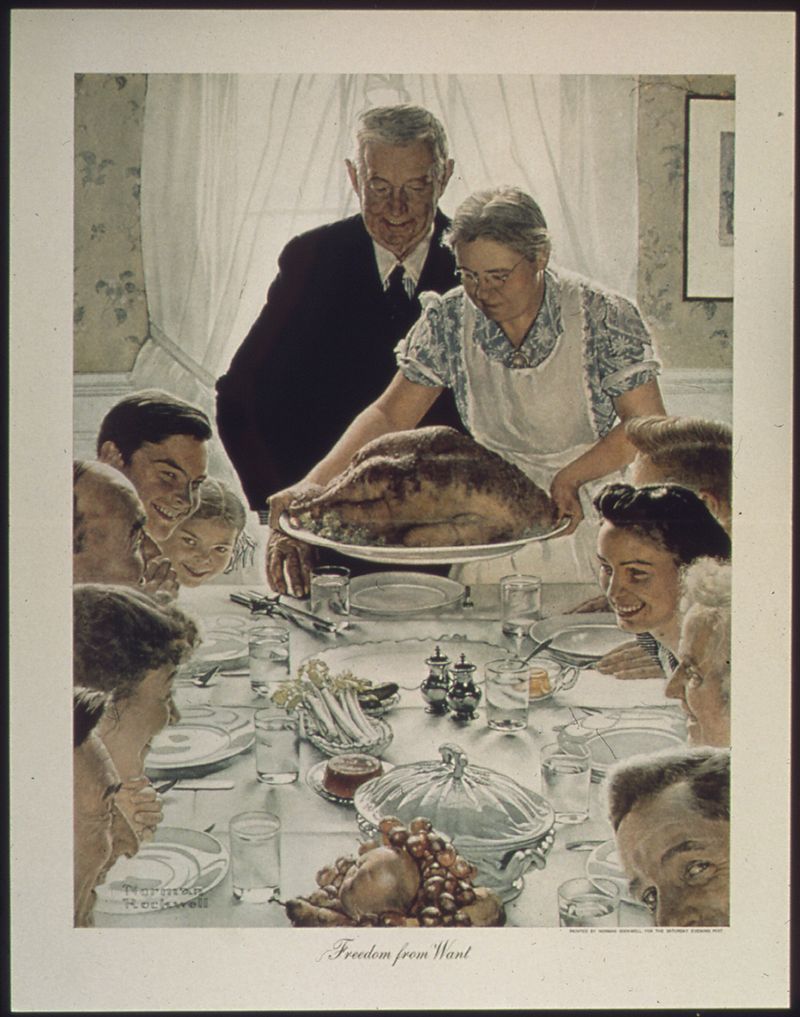

At the State of the Union address in 1941, Roosevelt announced that one of America’s four freedoms was the “freedom from want”(Roosevelt). The 1940’s became a time where Americans were frugal. It was a period of war and rations. In Normal Rockwell’s Freedom from Want, the table set at Thanksgiving is a plain spread without ostentatious display: celery stalks, cranberry sauce, Thanksgiving’s connotation of gratefulness rather than possession.

Contrastingly, Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans produced in the 1960’s displays a multitude of mass production, capitalism, and the desire for products that had solidified into American consumer’s minds.

The Pull and Allurement of the Materialistic American Dream

“In 1953, the net worth of the typical black household was just 20% of that of the typical white household”(Guilford 9).

The Pull and Allurement of the Materialistic American Dream

“In 1953, the net worth of the typical black household was just 20% of that of the typical white household”(Guilford 9).

The origins of the Younger family’s money revolve around old Walter’s life insurance. As Walter states, “That money is made out of my father’s flesh…” (Hansberry 575). The cold colored green paper often associated with greed and selfishness becomes alive--a symbol of a father’s undeniable selflessness for his family. The stark dichotomy between the two interpretations demonstrates the lower class struggle for an essential that can’t be replaced. Dreams for money are humanized. Money is characterized as generations of life and death, “working and working and working like somebody’s old horse...killing himself….”(Hansberry 577). For those in a lower class experiencing discrimination in the 1950’s, money--a motif of the American Dream--becomes even more than purchasing products, it takes on a precious ideation like a piece of gold; money not only contains the dreams of the individual, it also contains the dreams and sacrifices of the individual’s ancestors.

Exuding a sweet sickly expectation of opportunistic growth, the commercialized Dream torments the beholder seen in the loss of Walter’s investment. Ironically, the social burden and discrimination on the beholder heightens the American Dream's perfection, ensuing a toxic cycle of anticipation with disheartening results.

The Push and Betrayal of the American Dream

The 1950’s also witnessed the rise of television. “Before 1947, only a few thousand American homes owned television sets. Just five years later, that number jumped to 12 million. By 1955, half of American homes had a TV set”(Golden Age of Radio 16). Television established itself as a tangible status symbol and profuse presentation of the American Dream.

The Push and Betrayal of the American Dream

The 1950’s also witnessed the rise of television. “Before 1947, only a few thousand American homes owned television sets. Just five years later, that number jumped to 12 million. By 1955, half of American homes had a TV set”(Golden Age of Radio 16). Television established itself as a tangible status symbol and profuse presentation of the American Dream.

“Why don’t you buy a TV?...Everybody got one. Earl, Ba Bra...Jesse!”(Wilson 1604). The materialistic ideals of the American Dream subtly appears again in Cory Maxon. A Football scholarship, Navy recruitment, and television request illustrate the younger generation’s naïve headstrong pride in hope. Hope is written in human nature and propels the American Dream to withstand generations. A hardened Troy refers to money as a necessary infallible tool to survive, preferring to tar the roof. However, he once dreamed before. This is characterized through Troy’s unforgivable dedication to the game of baseball--one where he establishes his personal mottos and life declarations. Baseball has become a testimony of the American Dream; “...former baseball commissioner Bart Giamatti once wrote, baseball is "the last pure place where Americans can dream"”(Koprince 13). Troy, a player elite enough to play in the American major baseball leagues, dreamed of playing. He was denied. A bruised trauma lies unrestrained in Troy, magnifying an uncontained longing for an opportunity.

Baseball symbolizes a “deferred” dream that “dries up like a raisin in the sun”(Hughes 2). “I just wasn’t the right color. Hell, I’m fifty-three years old and can do better than Selkirk’s 0.269 right now!”(Wilson 1607). Regret, a consequence to uncontrollable societal constructs as a sidelined, underrepresented voice, burns inside Troy and contributes to his future skewed decisions: choosing infidelity, rashness, and selfishness.

Tenacity and Struggle

“For African-Americans, as for most people in the United States, their relationship with the American Dream is far more complex than one of either uncritical acceptance or rejection: we are continually coming to terms with the tenets of the Dream...” (Haggins 78). The American Dream exudes an elusive ambiguity.

Comments

Post a Comment